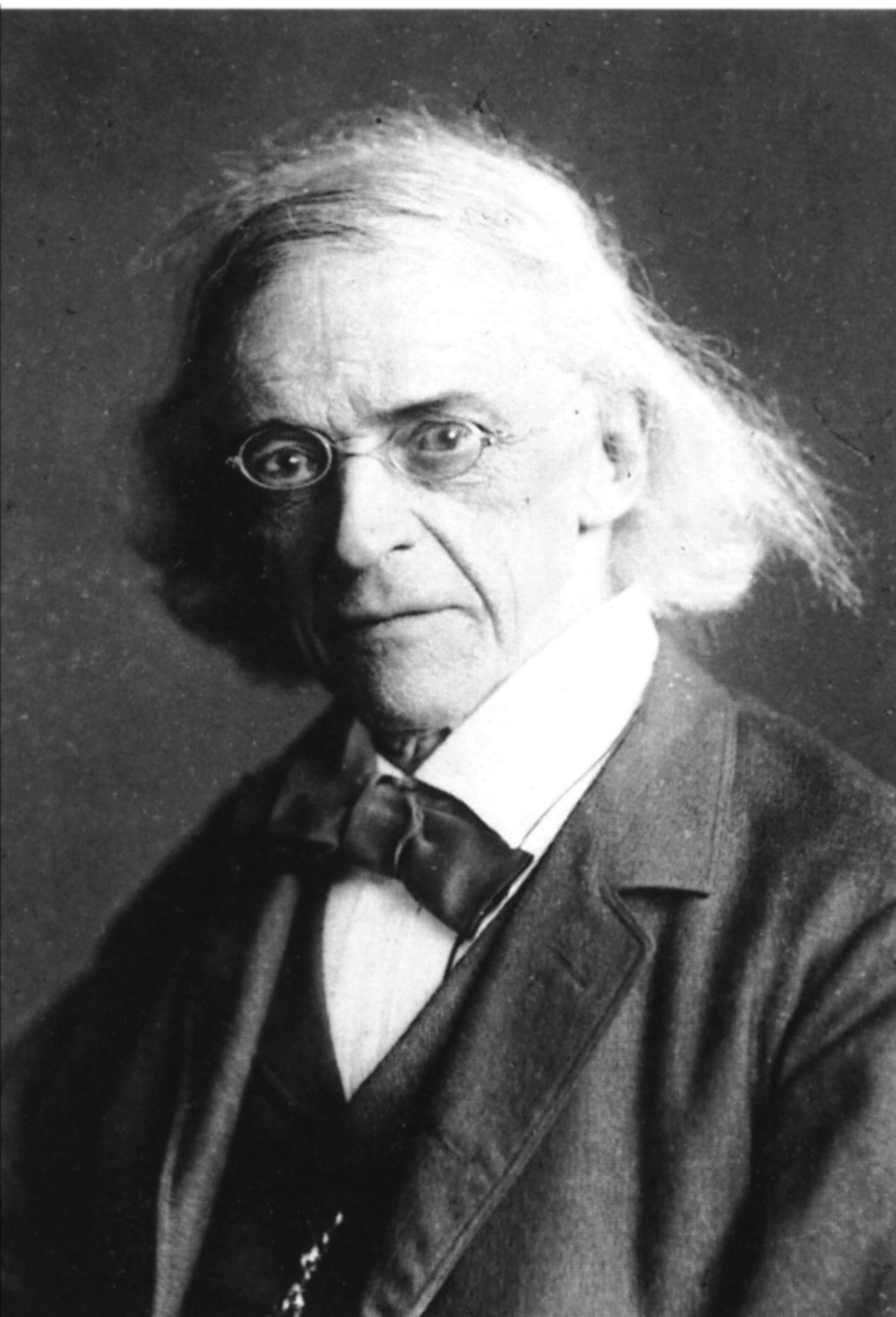

Theodor Mommsen Berühmte Zitate

„In dem Glauben an das Ideale ist alle Macht, wie alle Ohnmacht der Demokratie begründet.“

Ideale in der Politik. In: Morgen-Post, 23. Jahrgang, Nr. 289, Wien, 20. Oktober 1873,

Originalfassung: "Aber der Glaube an das Ideale, in dem alle Macht wie alle Ohnmacht der Demokratie begründet ist, [...]." - Römische Geschichte, Erster Band, Fünfte Auflage, Zweites Buch, Kapitel III, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1868, S. 317,

Zugeschrieben

„Jede große Zeit erfasst den ganzen Menschen.“

Römische Geschichte, Erster Band, Fünfte Auflage, Zweites Buch, Kapitel IX, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1868, S. 486,

Römische Geschichte, Erster Band, Fünfte Auflage, Drittes Buch, Kapitel XIII, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1868, S. 890,

Römische Geschichte, Dritter Band, Fünftes Buch, Kapitel XI, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1856, S. 429, DTA http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/mommsen_roemische03_1856/439

Römische Geschichte, Erster Band, Fünfte Auflage, Erstes Buch, Kapitel XV, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Berlin 1868, S. 233,

Römische Geschichte, Erster Band, Erstes Buch, Kapitel XIV, Weidmannsche Buchhandlung, Leipzig 1854, S. 136, DTA http://www.deutschestextarchiv.de/mommsen_roemische01_1854/150

Theodor Mommsen: Zitate auf Englisch

Vol. 4, pt. 2, translated by W.P.Dickson

The History of Rome - Volume 4: Part 2

Vol.4. Part 2.

The History of Rome - Volume 4: Part 2

Vol. 4, pt. 2, translated by W.P.Dickson.

The History of Rome - Volume 4: Part 2